The following was exclusively published by The Foggiest Idea on February 3rd, 2023. Interested in supporting The Foggiest Idea’s award-winning reporting and analysis? Click here.

BY RICHARD MURDOCCO

As her just unveiled $227 billion New York budget reveals, Gov. Kathy Hochul is once again taking an aggressive stance on forcing downstate suburbs to approve and build a significant number of new housing units in the coming years.

Unfortunately she apparently didn’t learn from her experience last year when she had to nix her controversial accessory dwelling unit (ADU) plan after it drew a firestorm of local criticism because this time around Hochul’s solution appears to be an even more ham-fisted attempt to break the logjam of housing affordability.

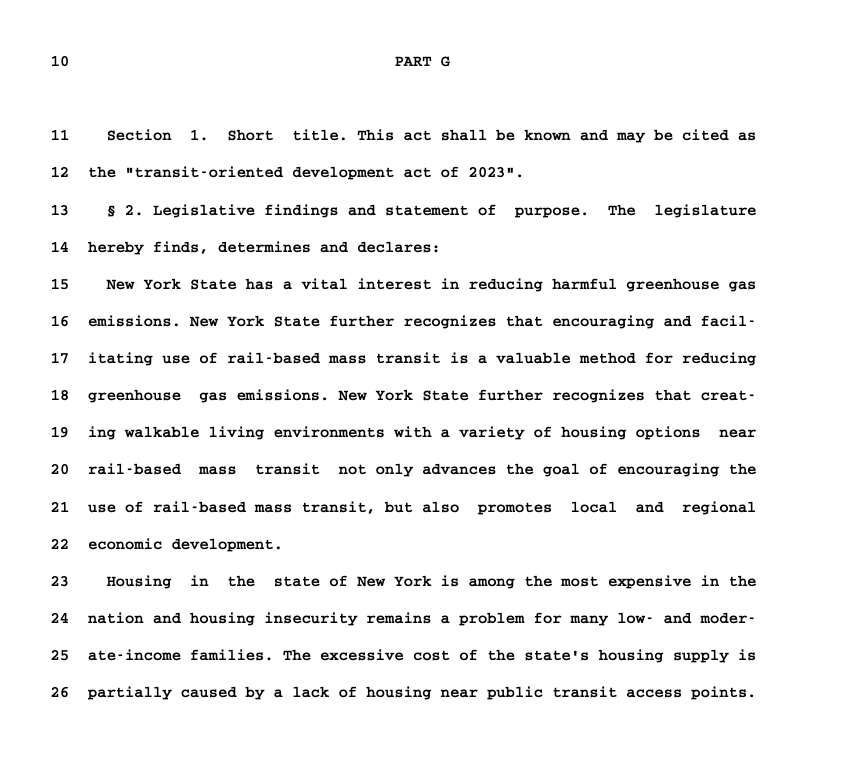

Her proposal, buried deep within the dense budget document, is labeled the Transit-Oriented Development Act of 2023. It calls for a tiered system of “minimum average density of residential dwellings per acre near transit-oriented development zones.”

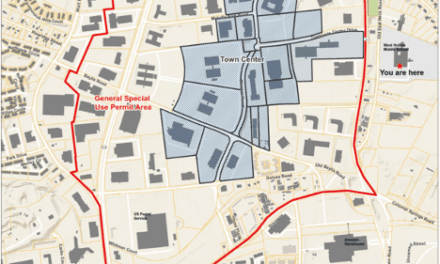

In short, the land that surrounds our region’s Metro-North and Long Island Rail Road train stations would be targeted for future housing projects by using zoning overlays that require developmental minimums. Localities would be given three years from the 2023 budget’s adoption to update their land use tools accordingly.

Here’s how Hochul’s proposal works:

Tier 1: One half-mile of any rail station up to 15 miles from the New York City line would be required to have zoning for a minimum of 50 residential units per acre.

Tier 2: One half-mile of any rail station 16 to 30 miles from the New York City line would be required to have zoning for a minimum of 30 units per acre.

Tier 3: One half-mile of any rail station 31 to 50 miles from the New York City line would be required to have zoning for a minimum of 20 units per acre.

Tier 4: One half-mile of any rail station 51 miles or more from the New York City line would be required to have zoning for a minimum of 15 units per acre.

As pointed out by Newsday’s editorial board the day after the governor’s proposal was released, every LIRR station within Nassau County falls entirely within Tier 1. That simple fact is alarming enough on its own, given what we know about how different those nearby neighborhoods really are, but an analysis of the other tiers’ respective minimums is no less forgiving.

Pictured: Under Governor Hochul’s budget proposal, areas within one half-mile of LIRR Stations would have to rezone to allow more residential units, scaled by their distance from the New York City limits. (Source: Richard Murdocco/The Foggiest Idea)

Suffolk County falls within the Tier 2 requirements for 30 units as far out as Hauppauge. By the time Tier 3 begins, you’ve already gone east of the William Floyd Parkway into places like Manorville and the compatible growth area of the Pine Barrens.

Typically Newsday’s editorial board is open to supporting housing development here as a matter of economic necessity and as a way to address the Island’s pressing social needs. But in their Feb. 2nd editorial headlined “Hochul budget has LI flaws,” they lamented that not only did the governor double the required minimums from what she talked about last month, but they also complained that she is trying to “liberate” Long Island. As the editorial put it, our region is “under siege only by those making irrational demands to change suburban life.”

This new tiered-system follows on the heels of Hochul’s heavy-handed push for the creation of mother-daughter style units, sometimes called “granny flats”, as well as stand-alone accessory apartments on single-family plots. Her ADU proposal never got off the ground because it sparked a bi-partisan uproar from a wide range of suburban policymakers.

After that failure, rumblings of state intervention could be heard coming out of the governor’s mansion in Albany.

But now that the details are out, it will only be a matter of time until elected officials across Long Island, as well as the constituents they serve, collectively recoil. Although the new multi-tiered proposal allows exceptions where there are cemeteries, wetlands and the like, it offers few, if any, ways for local governments to wriggle their way out of meeting the mandated requirements.

So what if a locality simply doesn’t comply? The text is clear that the consequences won’t be pretty. The recalcitrant municipality would undergo something called a “transit-oriented development review process,” and be subject to potential legal action from the State Attorney General.

For builders who were denied approvals from localities, their complaints would not go unheard. In fact, they’d get special attention because, under Hochul’s housing proposal, “any party aggrieved by any such failure or denial may commence a special proceeding against the subject city” in the State Supreme Court to “compel compliance.”

Pictured: Introductory Language from Part G of the NYS Proposed Budget for FY 2024 which introduces the Transit-Oriented Development Act of 2023. (Source: New York State)

And if the local government’s denial was found to be out-of-bounds, the court could force compliance. For example, if the Town of Smithtown squashed an application to build an apartment complex around the LIRR’s train station in St. James, the court could override the town board’s decision.

The main concern, of course, comes down to Long Island’s infrastructural limitations and environmental considerations, but on these fundamental factors the proposed text is relatively mum. From what we have seen so far, Hochul’s plan could unleash more rounds of legal battles while nothing gets built outside the courtrooms.

Inevitably, we can expect that housing advocates, urbanists and others who frown upon the supposed excesses of suburbia will paint Long Islanders with the broad-brush argument of close-minded NIMBYism. And recent market dynamics have only added fuel to their fight.

The latest data show that the median sales price of a Long Island home in 2022 was nearly two thirds higher compared to 2013. On the East End, prices grew even faster, with homes in the tony Hamptons going for 87.5% more than what they did a decade before.

Taken all together, a study from Point2 found that the price of an average home on Long Island increased a whopping $65 per day during the 10-year period between 2011 and 2021 – that’s $23,725 per year, or $237,250 in total.

So it’s quite clear that the region needs housing. But top-down policymaking from Albany that ignores the nuances of community-based planning and excludes local concerns is not the way to go. We can do better than that—and we must.

Richard Murdocco is an award-winning columnist and adjunct professor in Stony Brook University’s public policy graduate program and School of Atmospheric and Marine Sciences. He regularly writes and speaks about Long Island’s real estate development issues. Follow him on Twitter @thefoggiestidea.