The following was written for the Long Island Press on December 21, 2015. You can read the original here.

There has been an awakening in Long Island’s developmental zeitgeist. Have you felt it?

Suddenly it seems that regional planning has become a popular idea.

It can be heard from the soapboxes of development advocacy groups, op-ed writers and policymakers who, up until a few short months ago, dismissed the concept of geographic cohesion as an academic exercise that gets in the way of “local” progress. But now these folks are seizing on it.

It’s funny how for so long the marketing of the “brain drain” illusion fueled so many policy recommendations on Long Island–and now it’s being pushed aside in favor of “flavor-of-the-day” regionalism.

Mere months ago, those in the “smart” growth camp argued that less restrictive local development is what’s needed to curb the supposed exodus of millennials from our region. The reality is that millennials aren’t so much leaving, but that our region is experiencing a birth dearth. In short, how can anybody flee a region if they weren’t born here in the first place? It is on this shaky demographic ground that these urbanists first built their approach to solving Long Island’s woes. Only now are they beginning to backtrack on that narrative.

The shift is so large that even Mayor Paul Pontieri of Patchogue, long considered the benchmark of downtown redevelopment efforts by developers and smart growth groups, is placing a six-month moratorium on all development. This is not surprising. The village rapidly built upwards of 700 apartments without really addressing the long-term impacts of such growth. Now they want time to absorb the surplus they have created.

The change in policy is readily apparent, with Suffolk County adopting the Regional Planning Alliance Program and other initiatives to encourage more coordination. As such, the “think local” commentators and advocacy groups are jumping ship to stay relevant within the new broader policymaking environment.

Despite the pendulum swinging towards a regional cohesion that will unify many of the larger real estate projects that are being proposed, don’t expect the transition to be easy.

The sad truth is that Long Island’s leadership isn’t really cut out for regional thought. The little fiefdoms of Nassau and Suffolk counties are fueled by the “me-first” mantra of local politics, as well as the hard-headedness of residents who refuse to alter the status quo. As such, regional planning policymaking has always faced an uphill struggle. In its absence, a fervent parochialism has taken over, bringing out the best, and the worst on the Island.

Economically, our region stagnates while aesthetically it thrives. Long Island’s middle-class neighborhoods are pristine, schools near-stellar, but our current system of “build now, worry about it later” is far from sustainable. We simply are not creating the fiscal growth necessary to maintain so many political and jurisdictional fiefdoms.

Thus far, the solution for many of these economic concerns has been a loose adherence to urbanist values, in other words: increased density, walkability and sustainability. All these values are well and good. But while developers and advocates give lip service to these valuable principles, they have done very little to put them into practice. In a Suffolk analysis of completed transit-oriented projects (located near Long Island Rail Road stations), roughly only 23 percent of residents in those developments used the train to commute to work.

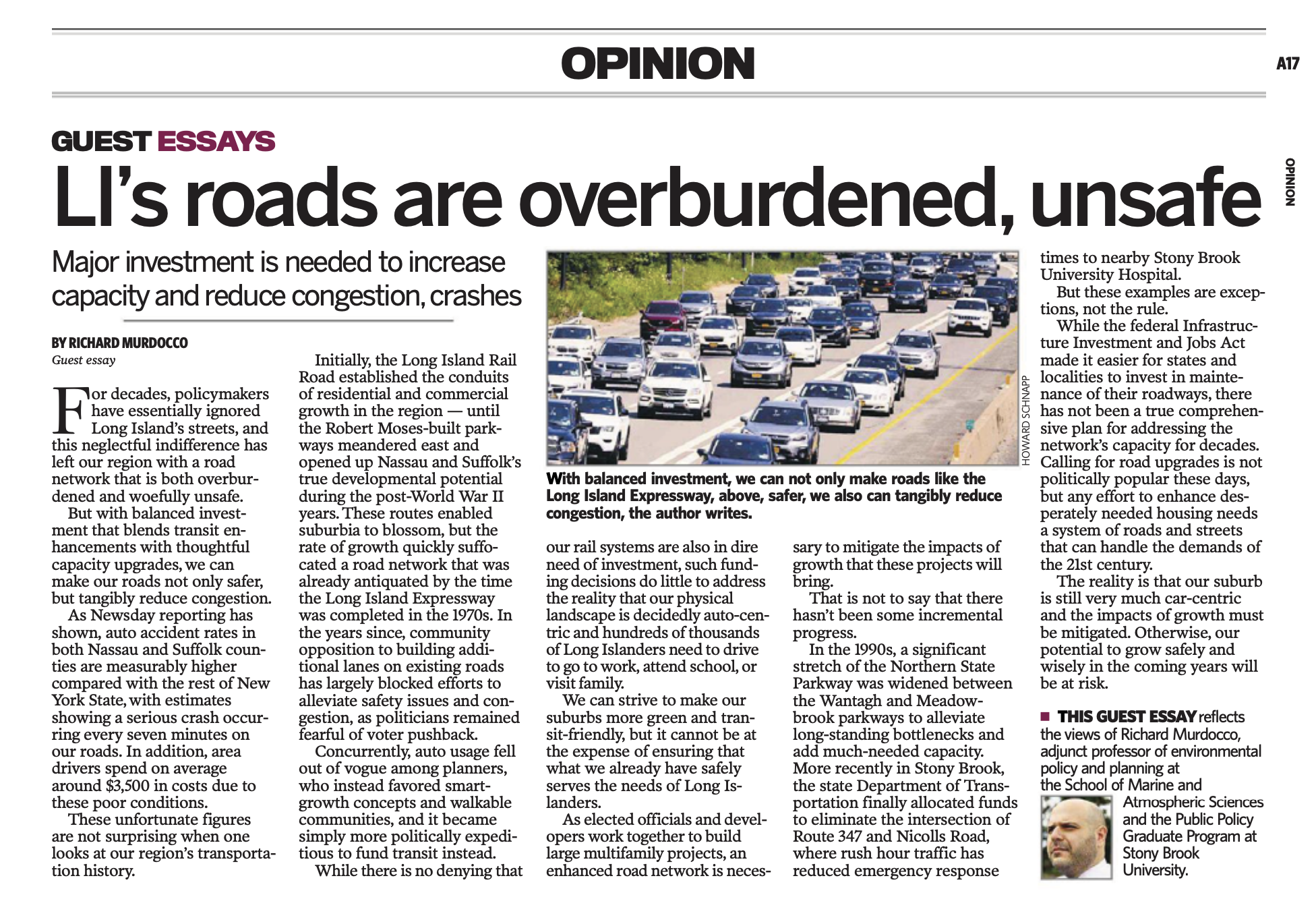

Long Island’s history doesn’t make matters any easier. When one looks back, it’s easy to see why the regional planner became a pariah by self-proclaimed localists who espouse urbanist values, yet do little to grapple with the reality of LI’s auto-centric suburbia.

Robert Moses, New York’s master builder, has cast a long shadow over any cohesive effort on Long Island. Moses is often cast in the public’s mind as a planner of colossal proportions—and the mere mention of his name taints the entire notion of large-scale thought in the mind of new-age urbanists. In reality, Moses was a builder who did not particularly enjoy the company of planners, who tended to have a little more compassion for the communities that were in his way, but that doesn’t matter much these days. Just evoking his name is enough to conjure up images of government bureaucrats steamrolling their way across Long Island, and so the concept of large-scale planning gets unfairly slammed.

After the era of Moses, Suffolk actively worked to contain the rampant suburban sprawl, which one can argue was facilitated by his accomplishments. Following Suffolk’s lead, local town offices created their own planning departments, which varied in degrees of effectiveness. Some municipalities took the task of planning more seriously than others, and aside from Suffolk’s advances in open space protection, Moses was one of the last truly geographic unifiers Long Island has seen.

It is by rebuking Moses where the proponents of the hyperlocal movement found their strength. Cities in particular benefited from this Jane Jacobs-esque approach to policymaking. Thanks to her grassroots activism decades ago, irreplaceable Manhattan neighborhoods like SoHo and Little Italy have retained their character. Moses would have demolished them for his cross-town expressway. Published in 1961, Jane Jacobs’ seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which criticized contemporary urban planning policy, helped inspire a community-oriented revitalization that preserved much of what would have otherwise been lost during the road building boom.

On the other hand, suburban residents have benefited from Long Island’s local point of view since the first Europeans reached the shores of Shelter Island. By the 1920s, countless private developments incorporated as villages for the sole purpose of maintaining their character and exclusivity. Of course, the problem is that this policy left the Island with a disgraceful, racist, even anti-Semitic legacy. Until 1948, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on another case, Levittown had a clause in its standard lease that said each new home could not “be used or occupied by any person other than members of the Caucasian race.”

Although the Island may still be one of the most segregated suburbs in the country, in more recent times local villages have experienced a renaissance of sorts. Developers have found the boundaries of Long Island’s villages easier environments to conduct business within, and thanks to advocacy and lobbying from groups like Vision Long Island, the transit-oriented philosophy caught on across Nassau and Suffolk counties. In what many would call a region inhospitable to big developments, this ability to ramp up density downtown in certain villages was a major accomplishment.

It is in this environment, with this history, that fervent localism is fostered at the expense of thinking broader and acting bolder.

As much as regional policymaking can be domineering in its execution thanks to the specter of Moses and his liberal use of eminent domain, local policymaking suffers from shortsightedness. Aside from municipal services, special districts and hundreds of school districts that are as redundant as they are costly, these multiple layers of government effectively block the large-scale, big-picture thinking that is needed in order to adequately address Long Island’s economic and environmental problems. Our water quality continues to be polluted, our transportation networks no longer meet our 21st century needs, and our idea of promoting economic growth is opening another big-box retail store.

In the end, it’s not so important whether growth is local or regional. All that matters is that it responds to community needs, and is based upon data-backed analysis. Unfortunately, only those who stand to gain the most from additional development are steering the conversation about Long Island’s future.

In the New Year, the goal should be not only to continue bridging the gap between local and regional approaches, but to solicit more input from the people who matter the most: the residents of Nassau and Suffolk counties. After all, it’s their future we’re supposed to be talking about.