The following was exclusively published by The Foggiest Idea on February 5, 2020. This piece was honored with a third-place prize for real estate reporting by the Press Club of Long Island in their 2021 PCLI Media Awards competition. Interested in supporting The Foggiest Idea’s award-winning reporting and analysis? Click here.

As the preservation of the Long Island Pine Barrens formally winds down, institutional indifference could put these vital woodlands at risk.

By Richard Murdocco

A recent announcement that the Long Island Pine Barrens are nearly completely protected is good news, but the future of this critical ecosystem encompassing over 100,000 acres overlying Long Island’s freshwater aquifer is far from ensured. The true work of open space protection is just beginning.

Despite strict land-use provisions enacted in 1993, untouched swaths of these pitch pine forests in eastern Suffolk County are still being threatened by developmental pressures and municipal indifference.

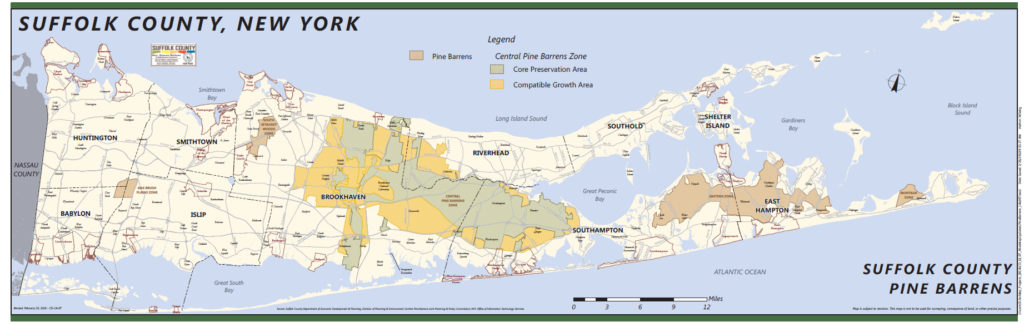

Today, over 57,000 acres within the Pine Barrens are designated as core properties where development is outright banned, while 48,500 acres are in the Compatible Growth Area (CGA), where tracts can be developed within certain parameters set by New York State. These provisions are reviewed and enforced by the Central Pine Barrens Joint Planning and Policy Commission, a state-created entity comprised of town, county and state officials.

And that’s where the battle lines are drawn.

Pictured: A map of the Long Island Pine Barrens region, showing both the core and CGA (Source: Suffolk County Planning, 2018)

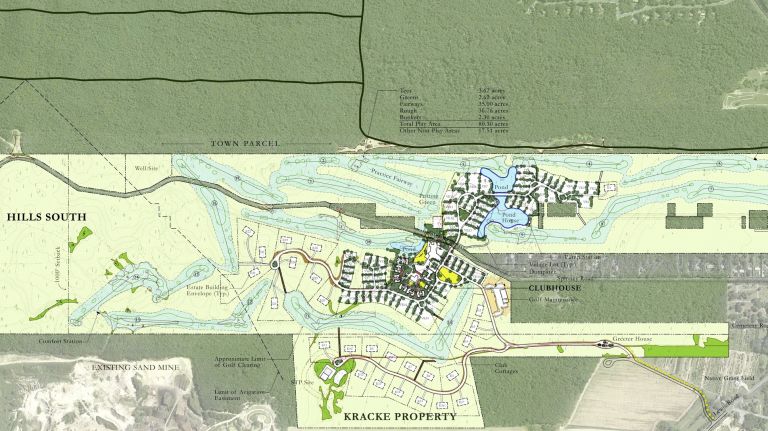

On a swath of 600 acres in the heart of the CGA within the Town of Southampton, Discovery Land Company, a Scottsdale, Arizona-based developer of resort communities, is pitching to build 118 homes, an 18-hole golf course, and a luxury clubhouse in East Quogue.

A previous version of the proposal, then called the Hills at Southampton, had been rejected by the municipality in 2017. Now the proposal is back with a new name and zoning designation: the Lewis Road Planned Residential Development.

The East Quogue project isn’t exactly being welcomed by locals. Actor Alec Baldwin, a Long Island native who has a home in nearby East Hampton, took it upon himself to record a public service announcement that railed against the project’s first iteration, calling it “the biggest and baddest development on Long Island.”

He isn’t off the mark – Allowing such a large project in the heart of the ecosystem is counter intuitive, especially given the sizable amount of taxpayer dollars allocated and longstanding commitment by state and local governments to protect the woods.

The ongoing saga highlights what the pine barrens faces in the years ahead: piecemeal proposals that threaten the ecosystem as a whole.

Green Acres by the Score

Decades ago, when thousands of trees were routinely being cleared for tracts of single-family homes and suburban streets, Suffolk residents finally had enough.

Riding the tide of rising environmentalism in the wake of Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book, “Silent Spring,” and seeing just how fragile the blue marble that we call Earth looked floating in space above the moon’s landscape thanks to Apollo 8’s “shot seen round the world,” Long Islanders embraced a renewed zeal for sustainability—and elected officials took action.

From imposing sweeping open space protections, to being the first county in America to formally ban detergents and DDT due to their adverse impacts on groundwater and wildlife, the environmental movement took root in Long Island’s suburbs.

After studying the link between land use and water quality, planners in Suffolk County recognized the need to take steps to translate their findings into action. It was paramount that any policy enacted would not only be broad in its reach, but also have the political teeth to be effective.

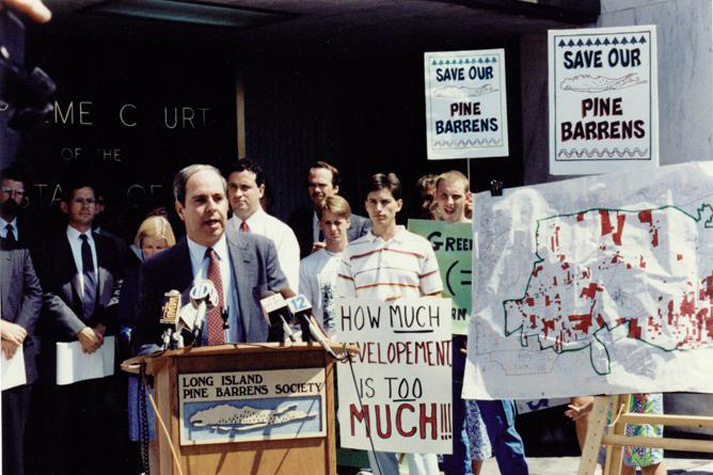

Environmental advocates launched one of the most successful public relations campaigns in the region’s history. Working along with Long Island’s developers, state, county and town policymakers came together. Showing its bipartisan support, State Sen. Ken LaValle, a Republican from Port Jefferson, co-wrote the Long Island Pine Barrens Protection Act with then-Assemb. Tom DiNapoli, a Democrat from Great Neck, who’s currently the New York State Comptroller. With a final push over the finish line by then-Gov. Mario Cuomo, the Pine Barrens were formally protected by New York State in 1993.

Pictured: Dick Amper, executive director of the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, holds a press conference on the protection of the Pine Barrens in 1991. (Source: Long Island Pine Barrens Society)

Decades later, the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, the non-profit organization that claimed stewardship of the issue, could announce proudly that its preservation goal of 100,000 acres had been surpassed.

“We didn’t mean to say we have all the land we want, because clearly there are additional parcels to be protected,” Dick Amper, the Society’s executive director told The Foggiest Idea. “But we must have done something right because we made it.”

Known for his dogged persistence and his unrivaled willingness to litigate, Amper believes that the days of buying a thousand acres at a time are over because local government officials have had to tighten their belts.

“I think they are in financial trouble and they are not buying land like they used to,” observed Amper. [Editor’s Note: TFI’s Richard Murdocco has worked with Amper and the Long Island Pine Barrens Society.]

Amper wanted to emphasize that Long Island taxpayers did most of the heavy lifting to protect the Pine Barrens by voting time and time again to spend money to safeguard open space and drinking water.

“The public encouraged the fight to keep money set aside for land and water to be used for that purpose, even if it required litigation,” Amper said.

On Jan. 21, 2020, a state Appellate Division unanimously rejected Suffolk County’s appeal to overturn a court order that it must repay nearly $30 million that the county had diverted from its sewer fund in order to balance its budget. The outcome represented a victory for the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, which had filed the original lawsuit in 2012 against former Suffolk County Executive Steve Levy.

“We prevailed,” Amper said, “but the days of aggressive land preservation seem to be over.”

Beyond the Core

According to John Pavacic, executive director of the Central Pine Barrens Joint Planning and Policy Commission, which has the combined duties of a state agency, a planning board and a park commission, the majority of the large swaths of the woodlands are now protected. So what’s next?

“Certainly, there is a need for focus on management,” Pavacic told TFI. He explained that the commission conducts controlled burns to prevent wildfires from occurring like the blazes in 1995 and 2012 that scorched thousands of acres on the East End. Setting aside concerns that the Long Island Pine Barrens might go up in smoke like Australia, development referrals keep Pavacic busy.

“We review most development in the compatible growth area,” he said. “Some cases come to commission for review, especially if they need a variance or hardship.”

Pavacic noted that there are still some areas of privately held undeveloped land in the core. Typically, these properties have been protected through include outright acquisition, or through the more complex use of the credits program, under which a land owner accepts a conservation easement that strips off the property’s development rights in order to sell those rights on the open market. In essence, it allows the transfer of development rights.

Recent expansions of the core area have included 1,600 acres near the Carmans River corridor in 2011, as well as about 800 acres surrounding the shuttered Shoreham nuclear power plant and 100 acres in Mastic, in 2017. The 2011 expansion also added 2,185 acres to the development-friendly CGA.

Dr. Lee Koppelman, a former regional planner for Nassau and Suffolk counties who now serves as head of the Center for Regional Policy Studies at Stony Brook University, told TFI that in general, the 1993 law has been very successful even when the political pressure to build continues to mount. According to Koppelman, the commission’s advisory committee, comprised of representatives from 24 organizations, does the real protection work. “It’s pretty iron-bound, and I haven’t seen any wavering on the members of the commission itself, or more importantly, the advisory committee.”

As more properties are added to the core and local opposition to development is galvanized, builders fear that the “transfer” part of the development rights mechanism won’t go as planned.

“The map, which is the most important aspect of this, has been amended on a number of occasions to add properties that weren’t in the core to the core preservation area,” explained Mitchell Pally, chief executive officer of the Long Island Builders Institute, a developers’ lobbying group.

“Our concern is that the lands that are not located within the core preservation area should be able to be developed,” said Pally, who has been actively involved with the designation of core and CGA properties in the Long Island Pine Barrens. “If they were supposed to be protected, they would have been added originally, or added when the map was expanded. Three times, government has expanded the amount of land to be preserved, all without making sure other lands can be developed,” Pally said.

“From our perspective, the biggest risk is the core,” he exclaimed. “Impediments are put up in the ability to develop property in the compatible growth area, which was not designated for preservation. It’s the most important thing we’re working on.”

Brookhaven Town Supervisor Ed Romaine, one of three Long Island town supervisors who sits on the five-member Central Pine Barrens Commission, disagrees with Pally’s assessment.

“People can build in the compatible growth area, and they build all the time,” Supervisor Romaine said. “They cannot bulldoze the entire lot and take down every tree. They have to adhere to the standards.”

Pictured: An entrance to Brookhaven State Park, a 1,638 acre property that was once owned by Brookhaven National Laboratory. (Source: New York State)

Romaine, a longtime public official who was in the Suffolk County Legislature in the mid-1980’s and from 2005 to 2011, is as well-versed in all matters Pine Barrens as anyone else on Long Island. He sympathizes with the developers’ frustration.

“They’re running out of places to build,” he said. But he believes that they should concentrate “on redeveloping, because much of what was built years ago needs to be redone…. There are limits to growth.”

Romaine told TFI about a Middle Island subdivision that was first approved back in 2004. “The guy sat on it through the recession, and now, sixteen years later, wants to finally build what was approved,” he said. “Much of the development that has taken place has come from old zoning approvals which the recession tampered down.”

“Now that the economy has turned around, people are building again,” he emphasized, “but on things approved 10, 20 years ago.”

“I am always very cautious about redevelopment and rezoning, but there has been more growth since I became supervisor,” Romaine said. “Zoning is forever, and when you rezone, it doesn’t mean it will be built.”

Things remain tricky because the law that established the Pine Barrens does allow for growth in the CGA, a fact that Romaine understands.

“It’s a property right, and if you move to take that right, you get sued and lose that suit,” Romaine said bluntly. “I’m very cautious casting a vote for a rezoning unless it’s a compelling case,” he noted. “At some point, we give zoning, and perhaps the zoning should expire.”

Koppelman said that the concerns of builders are legitimate, and he doesn’t see that tension waning anytime soon since anyone in the CGA has a legal right to build. “If a developer owns property in the CGA, they can file an application to develop it,” he said. “It is a battle between the environmentalists adding CGA to the core in order to protect that underground water,” Koppelman stated, mentioning that his original intention decades ago was protect the entire swath of 100,000 acres as undeveloped core.

As such, Koppelman thinks that more of the CGA should be outright preserved. “The challenge in our modern times is to gobble up as much as the CGA as possible,” the planner said, citing the purity of the groundwater beneath these properties. “Once you develop communities, particularly when they are dumping sewage into the ground, from an environmental stand point the property has lost it’s value.”

Regarding the commission’s role, Romaine believes that it will remain busy in the coming years, especially as problems like illegal dumping, invading southern pine beetles, or accelerating developmental pressure take center stage.

“The commission is busy every month,” Romaine said, “with people coming in asking for permission to do one thing or another. We’re constantly dealing with these issues because people would rather ask for forgiveness than permission.”

Pictured: A November 2017 graphic showing Discovery Land Company’s The Hills at Southampton, a controversial project for 600 acres in East Quogue. (Source: Newsday)

But no matter what happens on the ground, Long Islanders have shown they support measures to protect the aquifer beneath us. As the Pine Barrens Society’s Dick Amper pointed out, Suffolk’s first drinking water protection program was approved in 1987 by an overwhelming 84 percent margin.

“If we put another referendum for spending on water quality improvement, the people would vote for it by lopsided margins,” Amper said confidently. “It’s a really exciting story that the people who lived in such a developed, crowded place would take the initiative of saying, ‘Okay, the pavement stops here.’ ”

Now, the task falls to Long Island’s policymakers and citizens to ensure that the vital Pine Barrens will never be paved over for short-term gain.

Richard Murdocco is an award-winning columnist and adjunct professor in Stony Brook University’s public policy graduate program. He regularly writes and speaks about Long Island’s real estate development issues. Follow him on Twitter @thefoggiestidea. You can email Murdocco at Rich@TheFoggiestIdea.org.