The following was first published on The Foggiest Idea on August 8, 2017, and later published by The Island Now on August 10, 2017. You can read the piece on The Island Now here.

New York City, which consumes almost a billion gallons a day of fresh water, has turned its thirsty gaze to Long Island’s beleaguered aquifers to quench its needs as it closes an upstate reservoir for overdue repairs to the aqueduct system starting in 2020 and expected to last a year or two.

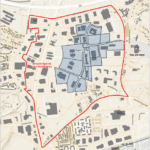

City officials have been rushing to replace the freshwater capacity that will be lost while the work occurs by planning to pump more than 33 million gallons daily from the water supply under Long Island. The issue is rapidly coming to a head as local policymakers in both Queens and Nassau County have to decide soon whether to tap into 68 wells across 44 sites in Jamaica that once served city residents before they were closed in 2007.

The issue isn’t if whether there is enough water to go around now, but what impact the additional draw of groundwater will have on communities in western Nassau such as Port Washington, Great Neck, Manhasset and Roslyn, where heavy demand is already straining local freshwater supplies.

Making the situation more complicated is that Nassau County lacks regional cohesion when it comes to protecting its drinking water.

Thanks to a patchwork quilt of municipal water providers, policymakers don’t even have a complete understanding of the condition of Nassau’s aquifer systems, so when NYC comes knocking to reopen its wells in Jamaica, the county, towns and villages have scant data-backed recourse. It’s not the same in Suffolk.

“Most of Suffolk County is served by a single water authority, but in Nassau County, there are about 40 water management organizations,” wrote Robert Brinkmann, a professor of geology, environment and sustainability at Hofstra University, in a 2015 Newsday op-ed. “While there is some coordination and cooperation, we do not have a coordinated approach to managing water. We all share one aquifer, but we have more than 40 straws dipping into the same glass.”

Long Islanders generally don’t take too kindly to the idea of outsiders coming into their local municipalities and asking for things—and that’s certainly the case here, given the notion of Queens taking “their” water.

But this time around, they have cause to be concerned, because being overly neighborly to New York City could have big consequences for Long Island’s sole-source aquifers.

Due to the unique geography under Nassau’s Gold Coast and South Shore, the local stores of fresh water have increasingly become threatened by saltwater intrusion, the mixing of potable fresh water with sea water. Saltwater intrusion has been a concern for local communities under the best conditions, but municipal officials, water providers and other stakeholders are worried that reopening Jamaica’s wells will only make an already serious problem worse.

Intrusion isn’t the only concern. The Lloyd aquifer, the region’s purest and most fragile source of water, may once again be tapped if the DEP is allowed to reopen the Jamaica wells. In Albany, State Senator Elaine Phillips and Assemblyman Steve Englebright have been trying to put a moratorium on the renewal of permits that allow pumping of the Lloyd within Queens County, but so far their effort has not been adopted as of the end of the 2017 legislative session.

Even worse, if the City reactivates the dormant wells, the increased demand on the aquifers can shift the flow of 150 or so contaminated plumes from Nassau’s Superfund sites, spreading tainted waters even further under the county’s communities. And they are just the toxic plumes Long Islanders know about.

In the past, the United States Geological Survey monitored all these hydro-geologic conditions thanks in part to financial backing from Nassau County. In typical Nassau fashion, however, the county balked at paying the USGS as it sank under its own rising fiscal pressures, so local taxpayers have had to raise the needed funds to cover the ongoing studies of intrusion themselves.

The City has said that the reopened Jamaica wells would serve as an “insurance policy” to meet higher water demands while its reservoir undergoes remediation work, but that has done little to assuage the fears of Long Island policymakers.

Meanwhile, Hempstead Town Supervisor Anthony Santino didn’t mince words in his June letter to City officials.

“I want to send a simple, yet strong message to the New York City Department of Environmental Protection: Don’t foul our water. Restarting the dormant wells in neighboring Queens could harm our drinking water. This decision puts the health and safety of more than 3 million Long Islanders at stake.”

The proposal has gotten more favorable local coverage in the City than on Long Island. In May, the Queens Chronicle wrote that the DEP’s initiative would likely get a good reception in Southeast Queens because groundwater tables in the area have reportedly risen more than 35 feet since the pumping stopped in Jamaica. The publication argued that the lack of pumping, combined with poor drainage, has resulted in several neighborhoods becoming vulnerable to flooding in even brief showers.

Officials in Port Washington weren’t that sympathetic.

“We need to protect ourselves from unhealthy shifts in the water table, saltwater intrusion and redirection of significant plumes of hazardous pollutants,” said David R. Brackett, the Port Washington Water District commissioner, in his newsletter. He said that without “state-of-the-art hydraulic modeling” it is impossible to project where the underground plumes will go.

Brackett is right. Accurate modeling is key to fully understanding this issue. If Nassau had a regional water authority like the one in Suffolk County, then resources for conducting comprehensive studies would be more readily available when they’re needed the most.

As always with Long Island’s aquifers, data-driven policy isn’t just sound planning practice, but an environmental necessity.

This time around, it’s the City of New York that poses a threat to our drinking water. What if next time it’s something more insidious?

Richard Murdocco regularly writes and speaks on Long Island’s real estate development issues. He is the founder and publisher of The Foggiest Idea, an award-winning public resource for land use in the New York metro region. More of his views can be found on www.TheFoggiestIdea.org or follow him on Twitter @TheFoggiestIdea.

You can email Murdocco at Rich@TheFoggiestIdea.org.

I still remember a time when both water and land were plentiful on Long Island!

Beware the developers who care more about nourishing their pockets and less about keeping the air and water clean and healthful.

Rich does a great job of informing humanity about the wrongs in society. He needs more exposure of his work through the media, and less of the verbiage that is hidden in the unscripted historic albums of time.