The following appeared in New Geography as a featured article, as well as LIBN’s Young Island.

Eric Alexander, the executive director of Vision Long Island, seems to be popping up everywhere on Long Island these days.

He was recently quoted in “The Corridor Magazine’s” transportation and infrastructure issue as saying: “Academic conversations about regionalism is a ’90s thing.” Similar to his condemnation on “academic” commentary concerning the downtown redevelopment trend, Alexander made it clear in the piece that he feels a local, downtown-centric approach is the way to go.

Whether we like it or not, Long Island is a singular region.

If Long Island’s developmental future is divided and segmented municipality-by-municipality, we, as a collective whole, will fail. The Village of Rockville Centre, one of Long Island’s much-touted “cool” downtown areas, shares the same aquifer system as Rocky Point. If a company abandons their corporate headquarters in Lake Success, residents in Suffolk feel the economic blow. Despite claims to the contrary by special interests and stakeholders, we are one island. Our social, economic and environmental policies must reflect that fact.

It is in the interest of builders, developers and stakeholders for Long Island’s developmental future to remain both segmented and divided under the guise of “localism.” Divide and conquer, as the saying goes. When projects are looked at on a regional level, they are more heavily scrutinized, and their impacts are more thoroughly explored.

Here is a scenario: A small village on Long Island is welcoming the economic windfall a particular development is slated to bring, while five miles north of the village, an unincorporated area fears their shops will wither thanks to the influx of shops proposed. The village does as they please, approving the development. Now, the businesses in the unincorporated area lay stagnant thanks to the over-saturation of retail usage that the new development brought to the area.

It’s Urban Planning 101: You don’t build what you don’t need. Much of the debate concerning Heartland Town Square, which is proposed within the Town of Islip, is that its impacts will resonate far beyond Islip.

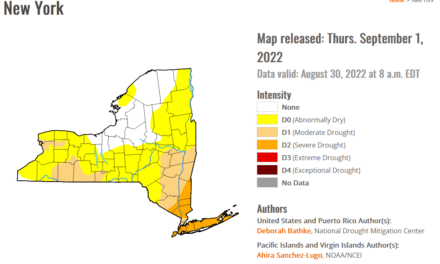

That’s the trouble with localism – it only benefits the locality, and often at the cost of other areas. Unfortunately for Mr. Alexander, some of Long Island’s issues are too big for the “locals know best” model he advocates for. Our fragile aquifer system transcends all geo-political borders, with poor land-use decisions in one town impacting water quality in the next.

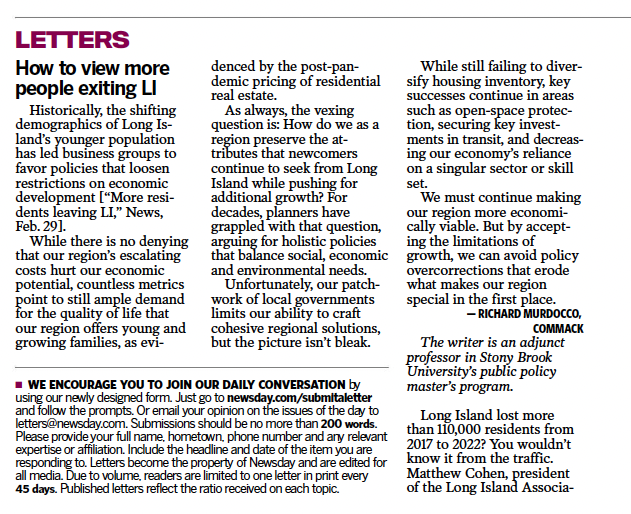

Our island is small enough for economic development policies to resonate far beyond the village or town level. While the Town of Babylon IDA and Town of Islip IDA squabble over wooing a manufacturing business, a lucky county in North Carolina will reap the rewards when they eventually steal them away from Long Island. It’s one thing for a village to build more housing options, but successfully raising a new multifamily development isn’t the same thing as quantifying and addressing our marked regional need for different types of housing.

Is it too “academic” to quantify our problems before taking the steps of addressing them? Is a protected aquifer system which supplies our region’s drinking water outdated like Zach Morris’ blocky cellphone or the Macarena?

Localism, at its worst, puts immediate needs first, and Long Islanders as a collective second. Part of the challenge we face as a region is the segmented and fractured governmental systems that prevent us from significantly making any progress. The biggest public works and sweeping acts of environmental preservation in this region’s history were executed thanks to a solid foundation of regional thought. The Long Island parkway system, LIRR and LIE weren’t built on the local scale. The preservation of 100,000 acres of Pine Barrens forest needed state legislation that trumped local zoning to be adequately protected. Suffolk County’s open space, water protection and farmland preservation programs weren’t locally sourced, homegrown policies, but rather models emulated nationally thanks to their breadth and regional scale.

Regionalism at its worst is characterized by monolithic bureaucrats making decisions without any local input. This is why a balance must be struck between both approaches that blend our local sensibilities with a comprehensive regional approach. The commonalities between Long Island’s various towns, villages and even counties warrant regionalism with a local twist. Our common aquifer is the largest common tie, while our surface bodies of water constrain our physical space. Economically, Long Islanders in both counties work and commute to the Island’s employment centers, which are concentrated in a few distinct locations, while all municipalities share neighborhoods that span the socio-economic spectrum. Given the common traits, a regional approach undertaken by municipalities, helmed by non-biased professional planners would serve both the local and regional good. For too long, Long Island’s development future has been staked out by stakeholders and policymakers with something to gain by swaying in one direction or another.

The best community planning efforts stem from public input, assessment of public needs and ample participation by the people who live and work in the area. The best environmental planning efforts use data and scientific study to advance the goals selected. A regional approach takes the best of both these approaches, and balances the needs of a region in a comprehensive manner.

A local approach works under certain circumstances. When a neighborhood needs a community center or seeks to improve the quality of life, the approach to development should be local. However, if the locality proposes development with impacts that resonate far beyond its municipal borders, a regional approach must be taken.

There is a reason why conversations concerning Long Island’s future must be academic, Mr. Alexander. We all feel the impacts of poor development choices. Sound regional planning isn’t something to dismiss as a ’90s thing, but rather, should be embraced for the betterment of Long Island’s future.